Pity and Terror: Picasso's Path to Guernica

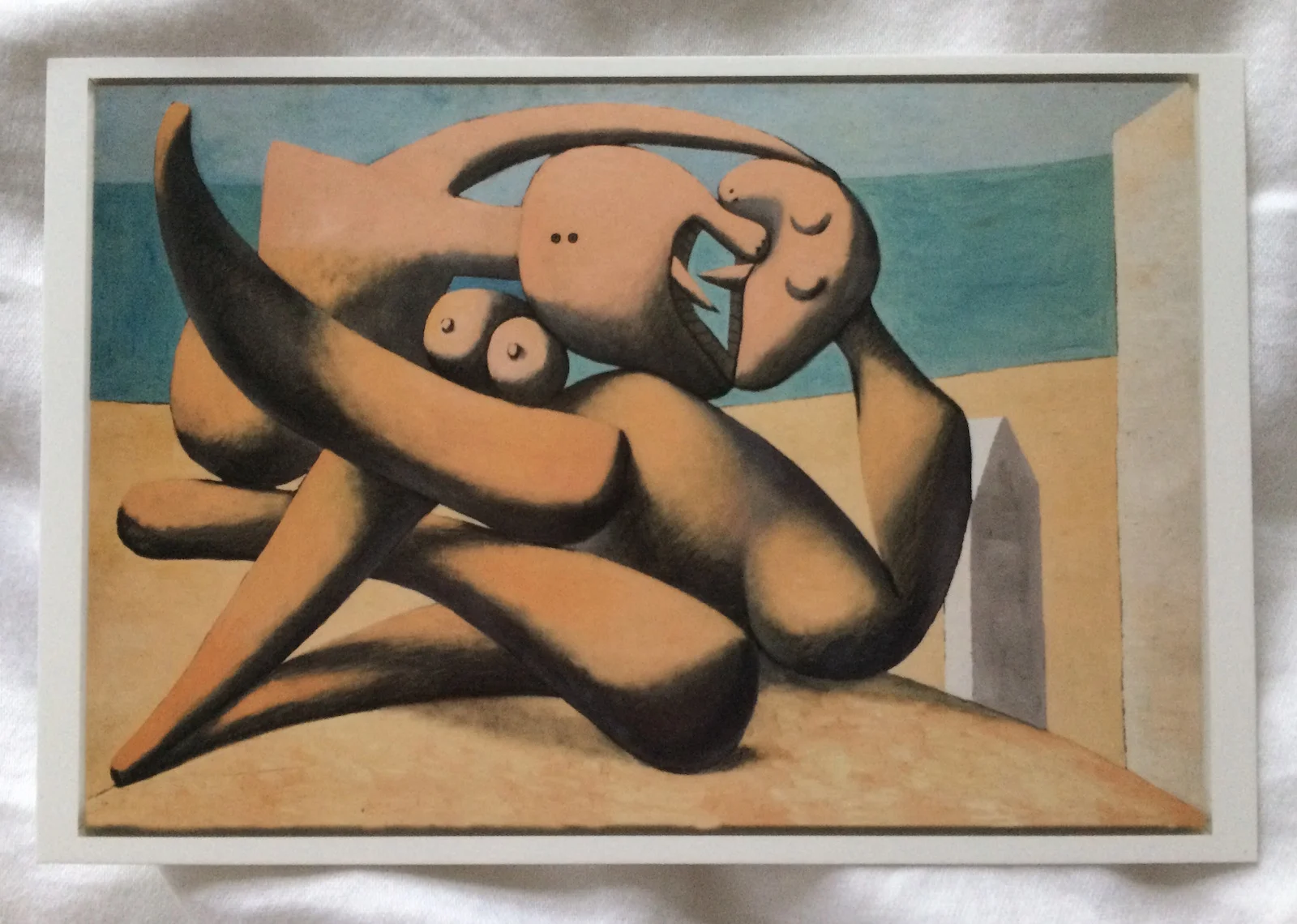

Pablo Picasso (1881-1973), Figuras al borde del mar, 1931 © Musée National Paris

The Madrid air is very hot; dry, drenching. Step into the chill foyer of the Museo Reina Sofía and a poster reads Piedad y terror en Picasso: El camino a Guernica – Pity and Terror: Picasso’s path to Guernica. It is an excellent temporary exhibition; taut, well-paced and engagingly curated. It is a rigorous and harrowing aesthetic joyride fuelled by the visceral excitement of looking at Picasso.

The exhibition marks the 80th anniversary of the bombing of Guernica, and of Picasso’s monumental work. Guernica was first shown in the Spanish Pavilion at the World’s Fair, Paris, 1937. The history of the atrocity, of the execution and exhibition of the painting, and the reportage which surrounded both massacre and Picasso are dealt with sensitively and comprehensively. The Reina Sofia has founded an archive devoted to the work. This is admirable, but the gripping power of the show is not archival or commemorative, but art historical; an engrossing examination of the relationship between Picasso’s magnetic, virtuosic genius and raw emotion; pity and terror.

It cannot have been easy, when dealing with works as momentous as Guernica and a legacy as complex as Picasso’s, to introduce abstract ideas other than those so deftly handled by Picasso himself. The power of the paintings and the energy of the artist take up enough space. Yet there is one, crucial question, imposed by the curators upon the works, which is not only fascinating but also has a place in a journal about concepts of beauty. Where do pity, terror and pain belong in Picasso’s work? Were they always a preoccupation of his? Guernica did not come out of nowhere. Once one begins looking for the thread of violence, it runs everywhere through his work. Jarring, exhilarating, grotesque, the visitor, still thrilled by his easy genius, cannot but as often be wincingly sickened. The question of sadism hovers over the spirit of the artist one encounters in those galleries.

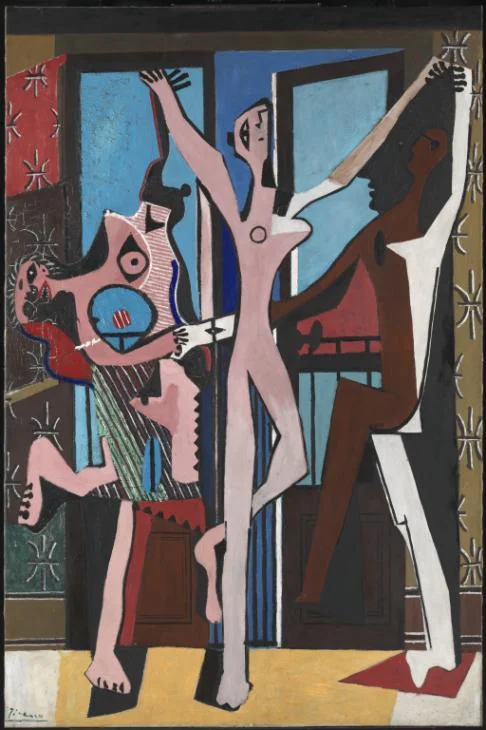

The visitor walks the visual and psychological road to, and beyond, Guernica through the rooms of both the Reina Sofia and of Picasso. Can one see in these early interiors, still lives and windowed rooms the kernels of claustrophobia, that room which in Guernica is spotlit in the moment of excruciation? Les Trois Danseuses hangs at the end of a long gallery. The viewer is suddenly party to an intimate, Bacchic scene, chaotic revelry in an apartment in the middle of the day, a work laced with reference to a ménage-a-trois, the suicide of a close friend and the sudden death of another.

Picasso, Les Trois Danseuses, 1925 © Succession Picasso/DACS 2017

The rooms of beach scenes are airier. Those grey-cream stone crescent figures against foreground and sky, abstract violence. Hideous spikes in a vacuum, puncturing nothing but the empty horizon. Two lovers kiss, their tongues conical stone thorns. Paintings in a hauntingly light palette reduce the female face to several lines, a nose, an eye. They are very clever, but when looking at them, one feels as though something terrible has happened. Guernica, no surprise, is the wrenching crux of the hang. The terrible thing that did happen. The terrified eye moves from one part of the composition to the next, pity brimming from a tightness in the chest. The penny drops; violence, pain, the claustrophobia of the room, the brutishness of the bull, the distraught woman, these were themes all along. The gaze has shifted from the silently weeping lover confined to a chair, obese and mutilated seaside bathers, skulls on a table, to the inarticulate anguish of war, the household ruptured.

Then the rooms of weeping women. Picasso did not stop painting pitiable women after Guernica. He could not stop painting them. Bestial, contorted, miserable. It was as though something had been unleashed. The Civil War in Spain continued, and then in 1939, the year it ended, Picasso’s mother died and Europe was plunged into war. Grey pervades, as well as purple - bruised, thorn-tongued heads thrown backwards in anguish. I realised the muscles of my face were tense with unease before these paintings (the drawings are more frightening still), grimacing in sympathy with the tangible anguish. I felt as though I had been crying.

David Sylvester once wrote of how Picasso is best understood by looking at many of his paintings successively. His works are often striking riffs on problems of space or form which render the complex suddenly simple. His brilliant painterly executions, each succeeding the next, draw the viewer deeper into a certain mode of looking. This way, cumulatively, his virtuosic, viscerally exciting (and extremely humorous) character can be understood. This exhibition achieves a remarkable thing. It places Guernica within Picasso’s oeuvre. Simple, one might think, but it isn’t. The work is a phenomenal apogee, chaotic and perfect. It knocks the breath from your chest. I rather think it would still do this if Picasso had never painted anything else. This exhibition cleverly shows where the figures, heads, bull, horse came from. Thence the forms. The psychology is Picasso’s. Along the long road to Guernica, Picasso had sharpened his sensitivity to fat, sensuous, pitiable human frailty, to claustrophobic domesticity, to sex and death. There is a good Spanish word for it: morbo. That which is deathly, diseased, immoral, compelling, alluring, wrong. Somehow it is better than morbid because it sounds as though it combines morte and libido, and it is Spanish. As is the bull, and the grisaille, the pseudo-religious composition and so much else. In the way of a good argument, book or film, the exhibition leads the absorbed viewer around and then, with a shiver, the denouement does not need to be disclosed, it is already realised.

Piedad y terror en Picasso: El camino a Guernica.

Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofía, Madrid.

April 5 – September 4, 2017